Pat Beall

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

12:00 a.m. Saturday, Nov. 19, 2016 Southern Palm Beach County

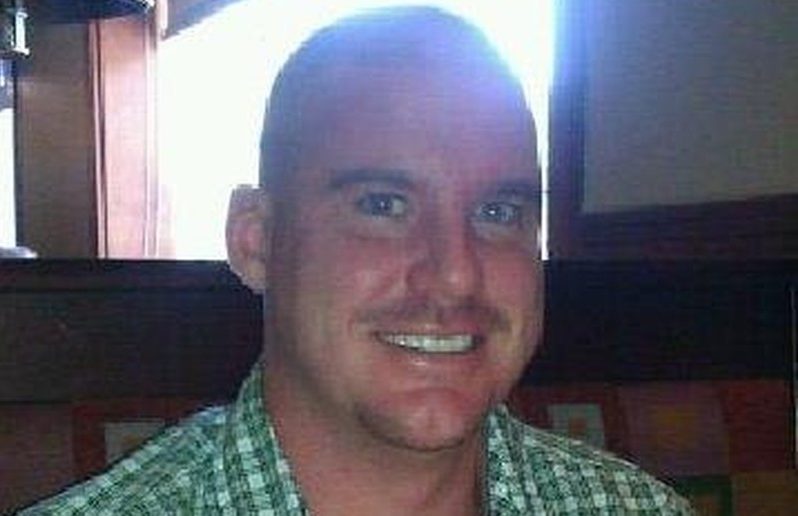

Gregory Gartside was first to fall.

The year wasn’t an hour old in 2015 when the Florida Atlantic University student’s parents returned from a New Year’s Eve party to find their son had overdosed on heroin.

Roughly once every other day last year, a heroin-related or fentanyl overdose claimed the life of a man, woman or teenager in Palm Beach County, more than all fatal traffic crashes and almost double the number of homicides.

Young mothers who doted on their children lost their lives to the needle; so did young men from wealthy families, Iraqi war veterans, ex-cops and drug counselors.

Parents discovered their dead children. A 10-year-old boy found his dead father. An 8-year-old found his mother.

People died alone in cars, or in the locked bedrooms of sober residences where they had sought sobriety.

Mostly, though, they died quietly in their home, in their bed, a door or two away from family or friends.

Nationwide, the heroin body count rivals the number of young Americans who died at the height of the Vietnam War.

But the killer of this generation has not prompted marches in the street demanding change. No one is packing city hall pushing for expanded treatment. The faces of the dead are not on the nightly news.

They remain invisible, victims of addiction’s stigma as well as the disease, rarely mentioned by name and almost never seen.

Overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly young and overwhelmingly middle class, many traveled from other states to get treatment in Palm Beach County, long recognized as one of the major recovery destinations of the world.

For some, it would be the first effort at recovery. For others, it was the latest bid for help in a years-long struggle.

They died all the same.

Addiction is a poorly understood brain disease. People cannot argue, love or threaten someone out of an addiction, any more than they can argue, love or threaten someone out of diabetes.

As with other chronic diseases, it is a disease with an element of choice. Type 2 diabetics fall ill if they eat the wrong food or fail to exercise. They must choose to control their blood sugar.

Similarly, heroin addicts must first choose to seek sobriety if they hope to live.

Yet the drug rewires the brain in such a way that it becomes increasingly difficult for a user to act in his or her self-interest. Relapse is common — just as with smoking — and appears to be more likely with powerful opiates such as heroin, among the most addictive substances known to man.

But a heroin relapse is especially cruel: People who got clean are at much greater risk of dying if they go back to the drug, because their bodies are no longer able to tolerate the dose they used to take.

The toll is staggering.

In Florida in 2010, a person with heroin poisoning showed up at a hospital emergency room about every two days.

In 2015, it was one every 90 minutes.

That is only heroin.

Once in the body, heroin converts to morphine almost immediately. In Palm Beach County, the medical examiner says most morphine overdoses reflect heroin use.

Further, the Mexican drug cartels dominating heroin sales in the United States are mixing another narcotic, fentanyl, into heroin. At the street level, dealers can order fentanyl online from China and mix it themselves. Some don’t bother mixing. They add any powdery, non-narcotic substance and pass it off as heroin.

One hundred times more potent than morphine, a dose of fentanyl as small as a few grains of salt can kill, and quickly: People in Palm Beach County are dying before they have time to get the needle out of their arm.

Last year, heroin, fentanyl and morphine caused the deaths of 2,333 Floridians, medical examiners’ figures provided to the state show.

Yet the county and the state have moved slowly — and in some cases not at all — to acknowledge the scope of the epidemic, much less take steps to curb it.

Outside of medical examiners, who daily see the bodies behind the numbers, almost no one is fully counting the dead.

As a result, The Post has compiled the only comprehensive list of the epidemic’s local toll.

That’s in sharp contrast to the string of politically conservative small towns dotting the Appalachians, where even the smallest communities have moved to treat addicts and revamp law enforcement strategies.

In Huntington, W.Va., which keeps meticulous statistics on heroin use, Mayor Steve Williams shakes the hands of addicts he meets in drug-riddled neighborhoods — and then holds their hands a few moments longer. “‘I’m not going to let you go,” Williams said he tells the drug users.

“And that’s the message that we have to send to those in recovery,” he said. “This community is going to be around you, we’re going to embrace you, and we’re not ever going to let you go.”

By contrast, in one early meeting of the Palm Beach County’s Heroin Overdose Task Force, a member suggested buying drug users bus tickets so that they could leave town.

In Virginia, New York, Maryland, Kentucky, Ohio, Rhode Island and New Hampshire, governors created expert, statewide groups to monitor the epidemic and ordered state agencies to come up with solutions. Needle exchanges were created. Access to the overdose antidote Narcan was broadened.

Yet Gov. Rick Scott, who told Congress he has a family member who suffers from addiction, in 2011 abolished Florida’s state agency overseeing drug control policy.

Massachusetts’ governor declared a public health emergency after statewide heroin deaths grew by 68 percent between 2013-14.

Florida deaths from heroin alone — not counting fentanyl and morphine — soared by 125 percent the same year; Palm Beach County’s heroin deaths grew by 155 percent. But the surge of heroin-related deaths in Florida has not triggered a similar urgent declaration.

The most recent high profile state of emergency from Tallahassee involved the Zika virus, which, while serious, has yet to claim a Florida life.

And the butcher’s bill continues to grow.

Former drug counselor and Air Force engineer Clint Parker died on Dec. 5, the first of 22 who would lose their lives in the final weeks of 2015.

Nicholas Ricciardi would die with a copy of the Narcotics Anonymous 12-step book next to him. Fantasy football fan Jagger Sharpless died; so did Donreece Newman, the son of a local gospel singer; Christopher Folsom Jr., a father of 4-year-old twins, and Courtney Walraven, whose brother had died two months before and who was getting ready to go into a rehab facility.

And then the year rolled over.

And then the year rolled over.

In the first few weeks of 2016, former Lake Worth Christian School student Maggie Marie Saitta posted on Facebook: “Everything heals. Your body heals. Your mind heals. Your soul repairs itself.

“Your happiness always comes back.”

She overdosed one week later.

She was 18.